TVM 2$days

TVM Tuesdays is a weekly blog that offers a fun, new take on this age-old topic and financial education insights from Brent Pritchard.

Sign up for email notifications:

Finance Students Are So Over Overcomplicated!

It’s that time of year. This month, people are fetching their Pumpkin Spice Lattes. Next month, turkeys will be running for their lives while runners sign up for local Turkey Trots. On campuses around the world, students are busy studying for midterm exams.

Photo by Brent Pritchard.

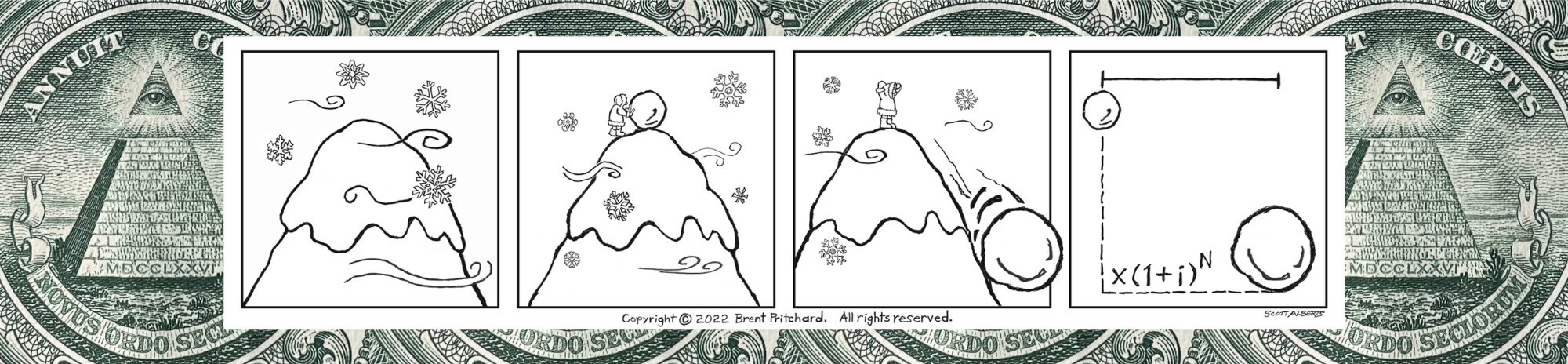

Here’s an excerpt from my book Would Your Boomerang Return? What Birds, Hurdlers, and Boomerangs Can Teach Us About the Time Value of Money (2023):

If you’ve ever participated in a race, then you know that there’s a total race time also called the chip time, and your average pace per mile. ROI is the equivalent of the total race time, that is the time from when your foot crossed the start line to when you cross the finish line. Do you see the problem with only providing someone with your total race time? When you sign up for a race you sign up for a distance, not a time. The time comes later. In this example, the only information this other person has is your chip time but no idea what distance you ran. For example, 5K, 10K, etc. Just as chip time is dependent upon distance, more information is needed to help someone make sense of the result.

On the other hand, i(RR) is like the runner’s average pace per mile. The average pace per mile provides information that can be interpreted and analyzed, regardless of the distance of the race. If the only race distance in the world was a one-miler, then the total race time and average pace per mile would be the same. But we know that foot races cover a wide variety of distances. Some are super short, such as a kids’ fun run, where participants are rewarded with cookies on the other side of the finish line. Race length goes all the way to ultramarathon endurance events covering 100 miles or more. Runners in these endurance events don’t usually have to wait until crossing the finish line to find treats, which are typically stocked at aid stations along the route.

Photo by Brent Pritchard.

Why do you think traditional finance textbooks are so overcomplicated?

Brent Pritchard is an author and college finance lecturer with over two decades of industry experience and cofounder of Boxholm Press, LLC, a family-owned-and-operated publishing company providing educational content, products, and services. He pioneers an innovative and approachable new way of learning and teaching the Time Value of Money as well as thought leadership in other business topics. His most recent book is Would Your Boomerang Return? You can contact him on his website here.

Are You a Passive-Aggressive Investor?

When I accepted a faculty position, in addition to swapping an office in Corporate America for a classroom, I traded a thirty-minute one-way car commute for a two-and-a-half-mile trip to campus. Thirty miles each way might not sound like much. But I made that commute for over twenty years! Two days ago, as I was commuting on my bike something happened (I wouldn’t exactly call it sidewalk rage) that got me thinking.

Photo by Brent Pritchard.

I had left church and would later realize that I had also left my helmet and water bottle behind. As I rode up a sidewalk in an unfamiliar direction, I noticed a couple walking ahead of me. I usually take the bike path on the road when I’m riding down the one way. Didn’t feel right to ride against traffic. That and I wasn’t wearing a helmet, so on the self situational awareness scale I was already on code orange.

As I passed this nice couple, I heard the man make a comment under his breath. I’ll let you use your imagination to choose how this ended similar to those books you may have read when you were younger. I will say that kind words were spoken. (Remember, I was coming from and going back to church.)

This got me thinking. Is passive-aggressive behavior really a bad thing? Bear with me. The word aggressive can carry a negative connotation, but I choose to focus on directness. In my mind, it sure beats the alternatives: passive or aggressive.

Now to money matters. And let’s flip the script. An “aggressive-passive” investment approach is characterized by one’s stretching to make those predetermined deposits (maybe early in life) when there isn’t much money coming in, so that later on that same person can passively watch their investments portfolio grow over time. I’d call a “passive” investment approach one where someone is waiting for others to save them from their financial doldrums. On the other hand, an “aggressive” investment approach is pedal to the metal investing. Not a bad thing if you can balance life and its responsibilities. Those loved ones you leave behind will thank you. Using these definitions, a “passive-aggressive” investment approach involves time wasted.

When are you going to put your money where your mouth is?

Brent Pritchard is an author and college finance lecturer with over two decades of industry experience and cofounder of Boxholm Press, LLC, a family-owned-and-operated publishing company providing educational content, products, and services. He pioneers an innovative and approachable new way of learning and teaching the Time Value of Money as well as thought leadership in other business topics. His most recent book is Would Your Boomerang Return? You can contact him on his website here.

I Take You to Be My Lender, I Promise to Pay You Interest or a Prepayment…Premium.

It may take two to tango, but it’s only going to take one borrower or mortgage banker (who forgets what life was like before receiving the lender’s money) to get fired up from this one.

Here’s an excerpt from my book Would Your Boomerang Return? What Birds, Hurdlers, and Boomerangs Can Teach Us About the Time Value of Money (2023):

All investors are focused on yield, whether or not investment yield takes the form of interest. For proof of this, we need look no further than loan documents and a provision that is commonly included and titled “Yield Maintenance.” It’s not called “Interest Maintenance,” even though interest is the form most, if not all, of the yield takes for the loan.

A mortgage lender may require that a borrower pay yield maintenance (aka a prepayment premium) if the loan is prepaid early to compensate the lender for the loss of the bargained-for yield. Again, not “bargained-for interest.”

And for the record, it’s not a “prepayment penalty.” One of many lessons real estate attorneys have taught me is that one can only get what another has to give. A lender gives a borrower the right to prepay the mortgage loan, and as a result, the borrower gets the flexibility that comes with holding an option.

Investors pay a premium for an option. In the case of a CML, the borrower controls whether to exercise the option and thereby prepay the loan. The agreement is governed by the loan documents that describe this right, among others, and create the bargained-for deal. Some people like to refer to the lender–borrower relationship as a “two-way street,” but I prefer the roundabout visual. It’s not the initial give and get that defines the relationship as much as it is the agreement that the getter will give and the giver will get. That’s what makes it come full circle. In the example, the getter received a right or option—but don’t stop short, there’s more—based on what was bargained-for. If the option is exercised, the only thing the getter can give is what was received, which is the bargained-for right to pay the required prepayment premium.

Still not convinced the correct term is prepayment premium? Are you a borrower?! If you still insist on calling it a “penalty” then know that it’s a penalty from the lender’s perspective. I know the argument: “But our profit from the sale of the real estate will be reduced to the extent of the prepayment premium.” That’s right, it will. And that’s why a holder of a traditional put option is willing to pay a premium that just might cut into their profit. Given the zero-sum nature of options, when the right is exercised one investor’s premium will result in another’s penalty.

Why would you break a (promissory note) promise and not call it what it is: a prepayment premium?

Brent Pritchard is an author and college finance lecturer with over two decades of industry experience and cofounder of Boxholm Press, LLC, a family-owned-and-operated publishing company providing educational content, products, and services. He pioneers an innovative and approachable new way of learning and teaching the Time Value of Money as well as thought leadership in other business topics. His most recent book is Would Your Boomerang Return? You can contact him on his website here.

Get the Book Today!

Would Your Boomerang Return? provides a fun, new take on how the Mathematics of Finance is learned and taught:

All-in-one resource: all the important information on this all-important topic in one place with chapters in the What and How sections that double as individual lessons

Ease of reference: includes the first-of-its-kind user manual for the Mathematics of Finance with chapters named after sections typically found in an actual user manual for quick look up

Simple and definitive tool: 3-Step Systematic Approach for analyzing and evaluating real-world Time Value of Money situations

Decision-making framework: 23 real-world Time Value of Money questions, space to work out answers, and a "baseball count" system to evaluate understanding of the different types of questions

An easy read: complete with sprinklings of real-life stories and maybe even an ounce of inspiration here and there

Sign up for TVM 2$days, a weekly blog that offers a fun, new take on this age-old topic and financial education insights from Brent Pritchard.