TVM 2$days

TVM Tuesdays is a weekly blog that offers a fun, new take on this age-old topic and financial education insights from Brent Pritchard.

Sign up for email notifications:

I’ll Take the Payment.

When you eat out, do you ask for your check or a bill? As far as I can tell, either appears to be correct. But for me, the word check has a positive vibe. There can be a negative connotation associated with the word bill. (Our oldest daughter is a waitress. I should ask her which is more common.) As it relates to the Mathematics of Finance, the word payment can, but need not, carry a negative connotation.

This image was created with the assistance of DALL·E and prompts from Brent Pritchard.

Some people, maybe those who ask for a bill in a restaurant, seem to think that there is only one way—think direction—to a payment. Like a two-way street, there are two ways to think about a payment when analyzing and evaluating real-world Time Value of Money situations.

Positive and negative. The different signs matter and inform which way the different payment types are flowing. For example, money received or withdrawn carries a positive (no sign) value, which denotes money coming into your hand. A negative sign denotes money leaving your hand, which is the case when money is invested or deposited.

Here’s an excerpt from my book Would Your Boomerang Return? What Birds, Hurdlers, and Boomerangs Can Teach Us About the Time Value of Money (2023):

There are two different payment types or classifications, and four different payment subclassifications. The acronym FAT, which stands for “Frequency, Amount, and Timing,” will help you tell what kind of payment you are dealing with. A payment with no frequency is called a single or lump-sum payment, which is represented by the variable PV or FV. When there’s frequency in the payment, you’re dealing with an even annuity, even perpetuity, uneven annuity, or uneven perpetuity. Amount and timing of the recurring payments tell you whether you’re dealing with an even annuity, even perpetuity, uneven annuity, or uneven perpetuity. A series of finite, even payments—even in terms of amount and timing—is considered an even annuity and represented with the variable PMT. An even perpetuity is a kind of even annuity with perpetual timing. When the number of the payments in the series is not even (equal) then you’re dealing with an uneven annuity. An uneven perpetuity has perpetual timing but payments that increase based on the growth rate (of inflation).

Negative signs only relate to certain TVM financial calculator inputs. Regardless of which way the money is flowing, you will always be working with positive (no sign) values for the variables PV, PMT, and FV in the building block Time Value of Money equations.

When did you first realize that three of the five primary TVM financial calculator keys are payment inputs, and that (positive and negative) signs matter?

Brent Pritchard is an author and college finance lecturer with over two decades of industry experience and cofounder of Boxholm Press, LLC, a family-owned-and-operated publishing company providing educational content, products, and services. He pioneers an innovative and approachable new way of learning and teaching the Time Value of Money as well as thought leadership in other business topics. His most recent book is Would Your Boomerang Return? You can contact him on his website here.

Stay in Your Own Lane.

Lots of people, when asked about their ability to operate a vehicle, will likely tell you that they consider themselves to be an above-average driver. But that’s impossible based on the law of averages!

International driving may just be the great equalizer. For example, you wouldn’t want to miss a Do Not Enter sign:

Photo by Brent Pritchard.

Here’s an excerpt from my book Would Your Boomerang Return? What Birds, Hurdlers, and Boomerangs Can Teach Us About the Time Value of Money (2023):

For questions involving multiple streams of cash flows, you can think bigger than the information provided in the question. For example, if you are asked to determine the amount of a savings account balance at a certain point in the future, you can extend the future value of deposits and even the future value of withdrawals to that point in time. You’re keeping the different payment types in their own lane so that you can get to a point in time where you can add or subtract or compare money. When you wrap your head around this point, it opens things up and makes thinking about Time Value of Money questions more manageable. Remember that you possess the Flux Capacitor of Finance, (1 + i)^N, which allows time travel in the context of the Time Value of Money by way of “indifferent lines.”

And speaking of streams:

Photo by Brent Pritchard.

(It’s not uncommon for runners to maintain an ever-changing mental list of “Top 5 Runs.” Today’s made the list!)

Where are you in your journey of acquiring the skills necessary to apply the Mathematics of Finance?

Brent Pritchard is an author and college finance lecturer with over two decades of industry experience and cofounder of Boxholm Press, LLC, a family-owned-and-operated publishing company providing educational content, products, and services. He pioneers an innovative and approachable new way of learning and teaching the Time Value of Money as well as thought leadership in other business topics. His most recent book is Would Your Boomerang Return? You can contact him on his website here.

Learn to Count Your Days.

Prior to when teaching and a desire to expand my influence outside of Corporate America won the day, I worked as a commercial mortgage loan officer for the real estate arm of a global life insurance company. One of my favorite mortgage bankers and someone I’m proud to call a friend to this day is Peter Dailey. (In case you’re wondering, this isn’t his real name.) Speaking of days, let’s discuss day-count conventions.

Here’s an excerpt from my book Would Your Boomerang Return? What Birds, Hurdlers, and Boomerangs Can Teach Us About the Time Value of Money (2023):

The most common day-count conventions are 30/360, Actual/360, 30/365, Actual/365, and Actual/Actual. For each day-count convention, the last number or word represents the agreed-upon number of days in a given year, and the first number or word represents the assumed number of days in a given month. The day-count convention 30/360 is also known as the “banker’s year.”

The “banker’s year” assumes that there are 360 days in a year and 30 days in each month. The 30/360 day-count convention makes the math easy. Not all mortgage “bankers” are as good with math as Peter and need some help!

A mortgage loan is an example of a negotiated agreement, and the borrower and lender agree that for the purpose of calculating the simple daily interest rate, the assumption will be that there are 360 days in a year, and that for the purpose of calculating the simple accrued interest, it will be assumed that there are 30 days in each month.

In the inc shorthand for most mortgage loans, “c” would be 12 and the “n” would be 1. But this is really a 30/360 “banker’s year” day-count convention in disguise, since you could divide the simple annual interest rate by 360 (/360) and then multiply by 30 to ultimately get the true monthly interest rate: the “c” isn’t 360 because the loan document doesn’t call for daily compounding or 360 compounding periods within the time span of the simple interest rate.

Now let’s run the numbers using the inc shorthand “0.005, 1, 12.” If this were a mortgage loan that required monthly debt service payments with interest calculated and accrued based on a 30/360 day-count convention, you could back into the simple annual interest rate of 6% in an unconventional way using the day-count convention:

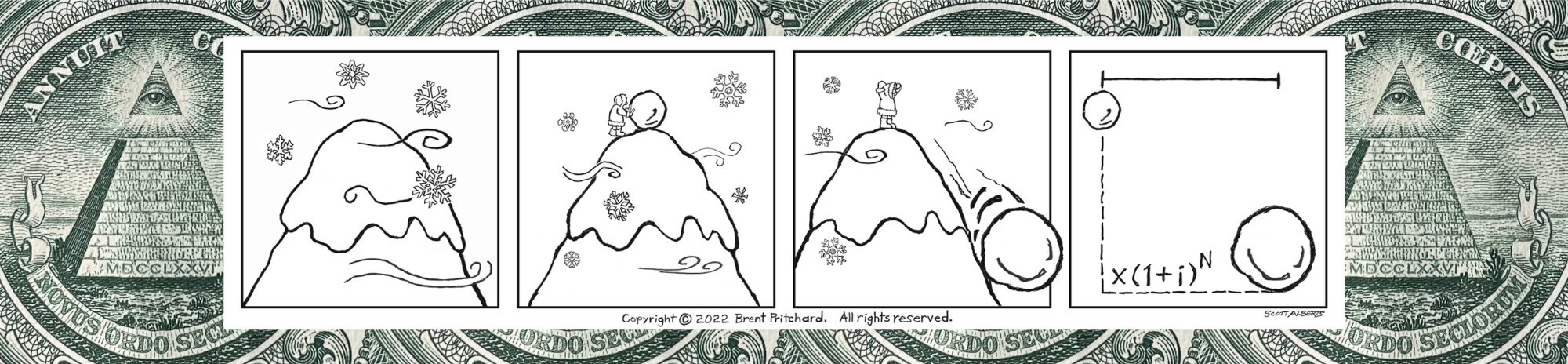

Illustrations by Scott Alberts. Copyright 2022 Brent Pritchard. All rights reserved.

You’ve been working with a “banker’s year” day-count convention all along, even if you didn’t realize it.

Today’s the day to learn more about day-count conventions, if you don’t have a handle on them already, because a finance professional who doesn’t know about day-count conventions is a finance professional whose days in the industry may be numbered.

Who is the first person to educate you on this topic of day-count conventions? (If not your finance instructor, then what’s up with that?!)

Brent Pritchard is an author and college finance lecturer with over two decades of industry experience and cofounder of Boxholm Press, LLC, a family-owned-and-operated publishing company providing educational content, products, and services. He pioneers an innovative and approachable new way of learning and teaching the Time Value of Money as well as thought leadership in other business topics. His most recent book is Would Your Boomerang Return? You can contact him on his website here.

Get the Book Today!

Would Your Boomerang Return? provides a fun, new take on how the Mathematics of Finance is learned and taught:

All-in-one resource: all the important information on this all-important topic in one place with chapters in the What and How sections that double as individual lessons

Ease of reference: includes the first-of-its-kind user manual for the Mathematics of Finance with chapters named after sections typically found in an actual user manual for quick look up

Simple and definitive tool: 3-Step Systematic Approach for analyzing and evaluating real-world Time Value of Money situations

Decision-making framework: 23 real-world Time Value of Money questions, space to work out answers, and a "baseball count" system to evaluate understanding of the different types of questions

An easy read: complete with sprinklings of real-life stories and maybe even an ounce of inspiration here and there

Sign up for TVM 2$days, a weekly blog that offers a fun, new take on this age-old topic and financial education insights from Brent Pritchard.